Ancient DNA gives insight into the mysterious Tashtyk peoples of Siberia

A friend of mine linked this interesting article to me a few days ago. Note that it is still a pre-print and still has to pass peer review.

First ancient DNA analysis of mummies from the post-Scythian Oglakhty cemetery in South Siberia

https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1993191/v1

Abstract

The Minusinsk Basin in Southern Siberia had unique conditions for the development of ancient societies, thanks to its geographical location, favorable climatic conditions, and relative isolation. Located at the northern periphery of the eastern Eurasian steppe, surrounded by the Altai-Sayan Mountains this area witnessed numerous ancient human migrations with specific types of interaction between outside and local archaeological cultures.

The genomic history of the human population of Southern Siberia from the Chalcolithic to the middle Bronze Age has been relatively well described in the recent genome-wide studies, while the genetic ancestry of populations, represented by diverse archaeological cultures of the Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages, remains a blank spot for modern paleogenomics.

Here, for the first time, we present two ancient nuclear genomes of the individuals buried in the Oglakhty cemetery (early Tashtyk culture, 2nd to 4th centuries AD). Our pilot study is undertaken within a multidisciplinary project on this noteworthy site with well-preserved organic remains and provides fresh paleogenomic data on the ancient societies of Southern Siberia.

Very, very exciting results for a steppe nerd like myself! This marks the first time since 2009, that I’m aware of at least, that we are getting our hands on genetic data on the Tashtyk culture. They were previously covered in the article Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people by C. Keyser et al., which showed that nearly all Tagar and Tashtyk culture samples had R1a-M417 and that genes for lighter features had a considerable presence in these populations.

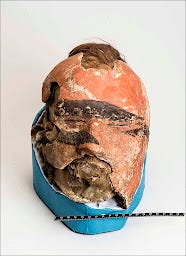

The Tashtyk culture from an archaeological point of view also happens to be one of my favourite material culture, and I will share some of the reasons why I find it so fascinating below. In fact, my own avatar here (at least at the time of writing) comes from a male from Oglakhty cemetery, where these samples are from.

Crazy to think that people such like him used to live deep in Siberia right? Not only that, by his time his ancestors had been living in those lands for well over a thousand years. The article in itself is quite short, so I’d suggest reading it first. However if you cannot be bothered, here are the most relevant parts.

Uniparental markers

MtDNA haplogroup analysis of the two adult Oglakhty individuals showed that they had a potential maternal kinship and belonged to the same I4a1 subclade of mtDNA haplogroup I. Previously, this subclade had been detected only once in the Minusinsk Basin – in an individual of the Karasuk culture (RISE 493, Sabinka II, grave 20) from the LBA (Supplementary Table 2) 1. It has not yet been found in any other analyzed individuals from the period of the Tashtyk culture or its immediate predecessor. Nevertheless, the I4 haplotype was described in an individual of the Tagar culture (Tchernogorsk archaeological site) 31. Interestingly, this haplogroup was also found in Viking graves of the 9th–12th centuries and is currently represented in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia 34.

The Y-chromosome haplogroup was identified for the male individual (KE9609) as R1a1a subclade based on M738, CTS3230, M747 polymorphisms. The R1a haplogroup was common for the Eurasian steppe and North Caucasus populations during the Bronze and Early Iron Ages. It became widely spread from the Andronovo cultural-historical commonality (17th − 15th centuries BC) onwards. This haplogroup is usually associated with the Indo-European migrations across Eurasia. The R1a haplogroup was identified in ancient burials at the Scythian and Sarmatian archaeological sites of the 1st millennium BC – first centuries AD.

So like the results from Keyser 2009, the Tashtyk male showed R-M417. In all probability this was R-Z93, the main haplogroup of Indo-Iranian peoples.

Autosomal ancestry

We merged the newly generated SNPs dataset for the two Oglakhty individuals with previously published genotypes of ancient inhabitants of the Eurasian steppe and Central Asia from the 1240K + HO database. We limited the study through the selection of those who are possibly more closely genetically/historically/geographically related to the Tashtyk culture individuals than others (Supplementary Dataset 1–2). This combined dataset was used for PCA, ADMIXTURE, and f3-statistics analyses to assess the genetic relationship between two Oglakhty individuals and other ancient Eurasian archaeological cultures.

Based on the PCA plot, we clearly showed that the Tashtyk specimens were genetically close to individuals from the precedingTagar culture as well as to inhabitants of Eastern Kazakhstan (in the period 1000 BC – early centuries AD) and Kyrgyzstan (first half of the 1st millennium AD) (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, among modern populations Tashtyk individuals (KE9609 and LC8544) share genetic ancestry with the present-day Chuvash people (Fig. 2B) who are predominantly native to the Volga-Ural region of Russia and are related to the Finno-Ugric group 39.

This relation to Chuvash however is just a genetic proximity on their PCA charts. This just implies relative similarity in terms of genetic components, rather than actually being closely genetically related in terms of sharing ancestry one way or the other. Considering this is still a pre-print I’d suggest to the authors to word it a bit differently in the published article.

Figure 2. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the Oglakhty individuals (KE9609 and LC8544) in comparison to 954 ancient and modern individuals inhabiting Eurasia (Supplementary Dataset 1). Modern genomes are represented by grey symbols, ancient genomes are colored. The Oglakhty human genomes analyzed in this study are shown by red circles and highlighted with the red area. (A) PCA plot for 954 ancient and modern individuals. (B) PCA plot for the two Oglakhty individuals and genetically closest ancient and modern individuals from the blue square on Fig 2A.

Figure 3. ADMIXTURE profiles (K = 11) of the Oglakhty individuals (KE9609 and LC8544) and human burials from archaeological sites of the Tagar, Karasuk and Afanasievo cultures, Sarmatians, ancient inhabitants of the Tian Shan foothills – the Zevakinsky burial complex, Tian Shan Hun and Saka. The Oglakhty human genomes analyzed in this study are highlighted by the red square.

Another suggestion to the authors would be to give an explanation of what the coloured components mean. As I can recognize some of the samples and thus make inferences such as pink = east asian, but not everyone will be able to. However as you can see in terms of components they are highly similar to the preceding Tagar peoples.

I should stress though that the amount of samples we have is not exactly large, and sampling a larger set of Tashtyk culture samples may reveal more variety in terms of genetic profiles. However the fact that two 3rd-5th century AD samples are nearly identical to samples from 900-700 BC is quite telling.

Origins of the Tashtyk

So now that we have this sorted out, let’s do what I do best. In order to explain the origins of the Tashtyk peoples properly, I’m going to set the stage by rewinding the clock to the start of the 2nd millennium B.C.

Around this time Indo-Iranian tribes were expanding from their homeland around the Urals across Siberia, Central Asia and the eastern European steppes. In the Minusinsk basin, Andronovo tribes of the Fedorovo type settled first. Fedorovo is a sub-type of the Andronovo, known in particular for their combination of inhumations and cremation. Around 1500 BC do we see the entry of Alakul tribes in this region, who then form the basis of the Karasuk culture. The Alakul group of Andronovo has a strong correlation with Iranian languages, making it quite likely that these new Andronovo populations were Proto-Iranic speaking peoples.

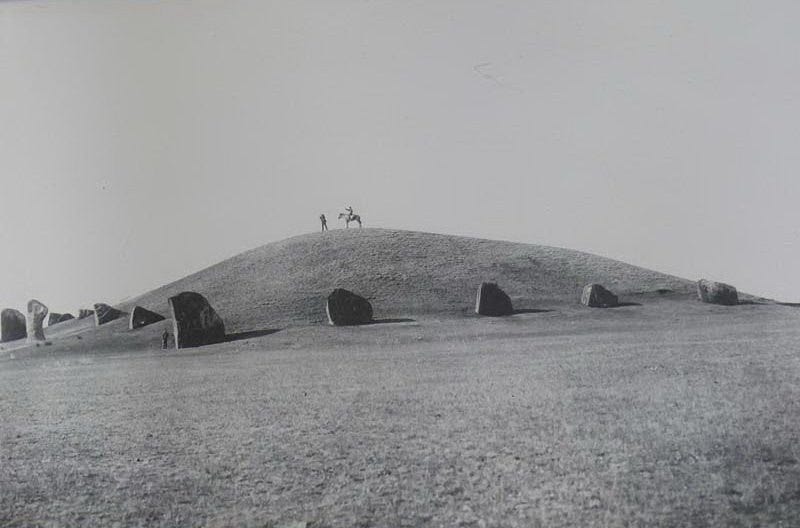

Megaliths with the Oglakhty range in the background

Both the Fedorovo and Karasuk tribes would practise subsistence economies which were a mix of animal husbandry and agriculture. However, due to a process of environmental adaptation, these tribes would progressively become more horse-centric, and eventually nomadic pastoralists on horseback. I have an older blog entry on the domestication of the horse, which might be worthwhile reading.

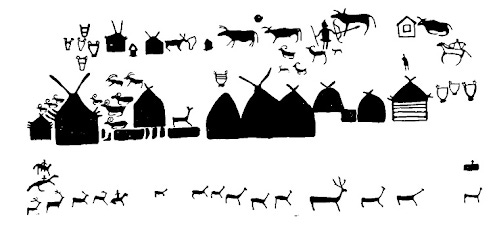

Around the onset of the iron age, circa 950 BC, do we see the development of the nomadic Scythian cultures, and the Karasuk played a significant role in the formation of this complex. In the Minusinsk basin do we see the development of a peculiar Scythian culture, the Tagar culture. This culture mainly stands out because unlike all the other cultures part of the Scythian horizon these people never adopted full nomadic lifestyles, keeping the sedentary agro-pastoral lifestyles of their bronze age Andronovo predecessors. We even have Tagar culture petroglyphs displaying their houses. Although we also have depictions of tents, thus their range of mobility might be a bit more varied. In general there were non-fortified settlements, fortified settlements as well as temporary settlements on pasture lands.

Here are some other petroglyphs:

Petroglyphs depicting skiers shooting arrows were also found in the Tagar culture:

While Keyser 2009 gave us information about uniparental markers and phenotypes, it did not give us much of a clue in terms of autosomal ancestry. Luckily several early Tagar culture samples were featured in Damgaard 2018. Furthermore, RISE492, from 300-200 BC is probably another Tagar culture sample given its location and timeframe, although it was not labelled as such by the authors. Using Vahaduo Admixture JS tool and the Eurogenes Global25 dataset, breaking down the samples in Steppe_MLBA/Northeast Asian/West Siberian and southern Central Asian ancestries, these samples looked like this:

Target

Distance

RUS_Sintashta_MLBA

MNG_North_N

RUS_Tyumen_HG

TKM_Gonur1_BA

RUS_Tagar:DA2

0.02401645

•

69.0

15.0

10.8

5.2

RUS_Tagar:DA3

0.02700320

•

64.0

11.0

18.2

6.8

RUS_Tagar:DA4

0.02404901

•

68.0

16.8

10.2

5.0

RUS_Tagar:DA5

0.02768129

•

62.0

21.0

13.0

4.0

RUS_Tagar:DA6

0.02146200

•

71.2

14.0

10.4

4.4

RUS_Tagar:DA7

0.03173492

•

60.4

13.2

16.2

10.2

RUS_Tagar:DA8

0.03504416

•

66.2

14.6

12.4

6.8

RUS_Tagar:DA9

0.02742521

•

69.4

15.0

15.2

0.4

RUS_Altai_IA:RISE492

0.04718338

•

66.8

21.8

11.4

0.0

Average

0.02951107

•

66.3

15.8

13.1

4.8

The first thing that stands out is that the Tagar culture have quite a high amount of steppe_mlba ancestry when compared to their contemporary steppe nomad relatives. In fact the steppe_mlba seen here is really only matched by Sarmatian samples. They have more steppe_mlba than some of the bronze age Karasuk samples for example.

Target

Distance

RUS_Sintashta_MLBA

RUS_Tyumen_HG

MNG_North_N

TKM_Gonur1_BA

RUS_Karasuk:RISE495

0.03168641

•

44.4

19.6

36.0

0.0

RUS_Karasuk:RISE496

0.05251518

•

66.0

22.6

11.4

0.0

RUS_Karasuk:RISE499

0.02278121

•

75.0

9.8

11.6

3.6

RUS_Karasuk:RISE502

0.02489450

•

56.4

17.4

23.6

2.6

RUS_Karasuk_o:RISE497

0.06717980

•

0.0

24.4

75.6

0.0

Average

0.03981142

•

48.4

18.8

31.6

1.2

This could be explained by two reasons:

The first one being that the Tagar samples were from a more northern location than the Karasuk ones. The Karasuk samples were situated in an area which during the later bronze age supported relatively large populations, and the area was also inhabited by the native Siberian/Mongolian pastoralist populations. The Tagar samples being to the north of this, could have lived in an area where most of their neighbours were hunter-gatherers with lower population sizes.

The second option would be that the Tagar culture samples are simply a mix of Karasuk-like peoples expanding northwards and assimilating the remaining Fedorovo tribes, with the Tagar carrying significant amounts of ancestry from them.

In my opinion it is a combination of these two factors that lead to the profile of the iron age Tagar culture samples. In such an event their genetic profile could perhaps be seen in this type of context.

Wonderful reconstruction of a Tagar culture male (Barsuchikha V, Kurgan 4, Burial 2) made by the wonderfully talented AncestralWhispers. Check out his twitter page here for the latest reconstructions!

The Tagar culture then lasted for centuries, pretty much throughout the first millennium BC. Quite a remarkable feat because a bit further south do we see a lot of movement and replacements of one Scythian culture by another. The chronology of the Tagar culture is currently established as a four-phase period [1]:

Large burial mounds such as the Salbyk mound were erected by the Tagar peoples.

During its construction the Salbyk mound may have looked more like this however:

"It is evident that these pyramid burials also involved the mummification of the body. The process of mummification can be reconstructed (Figure 9; B). The skeletal remains (skulls and separated bones), were exposed for some period of time then were buried in crypts (Tagarski Ostrov, Malaya Inya, Buzunovo, Kop’evo etc.). An attempt was then made to recombine the parts of the body, not always successfully (Tepsei VIII). The spine, hands and vertebrae were fastened with thin rods, to reconstitute the shape of the body (Medvedka II, Mayak, Sabinka etc.). Meanwhile the head was modelled in clay and fastened to the reconstituted body. The whole mannequin was then painted, clothed and provided with a mask (Kuzmin & Varlamov 1988). Similarly complex operations are found in burials in the Altai (at Bashadar, Pazyryk, and Ukok) (Grjaznov 1950; Rudenko 1960; Polos’mak 2001) and in Tuva (at Urbjun, Balgazin etc.) (Grach 1980). Although the mummies themselves did not always survive, traces of mummification have been discovered in various mounds in south Siberia dating from the first millennium BCE."

By the end of the first millennium BCE the ritual did not include the burial of mummies, but rather of dolls, filled with grass that are traced especially to the Tashtyk culture. They were dressed in clothing; their heads were covered with the painted masks; and a small sack containing burnt bones was put inside the body (Vadezkaya 1999). Smaller tombs constructed in the same way stand one against the other, each containing a single tomb constructed of slabs. There are also many tombs, particularly children’s graves, which are located within various sections of the barrows. If we compare the tombs belonging to the successive phases of the Tagar culture we can readily observe the close affinities between them in tomb structure, grave furnishings and funerary ritual. This implies the development of an indigenous cultural group over a period of ten centuries during which there were no abrupt changes in the economic, domestic or social patterns and no sudden displacements of large numbers of people. However, penetration of small groups of the population is not excluded.

The same article then summarises the Tagar culture as following:

The continuity of culture from the preceding Karasuk period and throughout the first millennium BCE implies that the people of the Minusinsk basin were undergoing development of their own rather than pressure from immigrants. The increasing size and complexity of the burials implies social changes. Burial rites and art reflects contact over a wide region of Eurasia, and China. Although this society was highly mobile, as it used mobile troops – horsemen, it also had deep and enduring roots in its own region. In conclusion, it is possible to say that the Tagar culture, which developed out of the traditions of previous Bronze Age cultures, created a unique culture with a complex local development and a long reach. In the first millennium BCE its separate elements penetrated nearby regions and on into China, and even further into Europe.

At the later phase of the Tagar culture, we have the rise of the Xiongnu. From historical records as well as archaeology we can infer that the area of the Tagar culture would have fallen under the Xiongnu dominion. This should correlate with the Tes’ phase of the Tagar culture. One can wonder how this occurred but in my opinion given the relatively small population sizes in this area I think this happened without too much of a resistance.

In any case, it is during the period of XIongnu rule that we see the Tagar culture develop into the Tashtyk culture, and then the Tashtyk culture persists during the Xiongnu collapse, ending around the 5th century AD during the Hunno-Sarmatian period of steppe archaeology.

Older theories

The discovery of the Tashtyk culture in a way is quite old, in the 18th century there already were reports of funeral masks being uncovered by treasure hunters. The Oglakhty cemetery was discovered in the early 20th century, initially by a local man who fell into one of the graves. Much of the academic works related to this site and the Tashtyk culture as a whole came from the earlier parts of the 20th century, and in some regards can be a bit antiquated. Although luckily it seems the Tashtyk culture has gained some newfound appreciation over the last few years with several new articles, often in English, having been published.

If one were to blindly trust the older archaeological descriptions of the Tashtyk culture, it would originate by way of the native, Samoyedic speaking Tagar culture people being conquered by a new intrusive population of mongoloid extraction. This Mongoloid population would be the elite of the society, and conveniently would only be represented by the cremated individuals in this society. The mixing of these two people at the end of the Tagar culture would lead to the Tashtyk culture. Due to this new superstrate, the “Samoyedic” Tagar peoples would then get linguistically assimilated into Turkic speaking populations, and thus forming the basis of the Yenisei Kyrgyz of medieval history.

Mask of Tashtyk male with “mongoloid” features

The two samples from this article show a bit of a different story however. On the PCAs provided they do seem to plot a bit away from Tagar, towards the direction of the Tian Shan Saka samples. They were still genetically very similar, as can be seen in the admixture charts. Even if the assumption that the cremated individuals were of different racial origin would be true, it would be strange for there not to be any mixing between the two and this not to be reflected in the buried populations, given factors such as downwards social mobility and population sizes.

This falls in line with more recent anthropological works, that suggest that the presumed east asian contribution that formed the Tashtyk was overblown, which was also referenced in this article. It also falls in line with archaeological assumptions about the Tashtyk being, predominantly, a continuation of the Tagar culture albeit with external cultural influences. To no surprise as this area was part of the Xiongnu empire.

This is a bit of a common trend in archaeology of (post-) scythian cultures by the way. Newer research seems to suggest a far larger degree of continuity between ~ 200 BC - 200 AD than initially assumed. This goes for archaeology, anthropology as well as genetics. I'll elaborate in a future blog entry.

The Book of Han mentions the lands of Jiankun/Gekun (堅昆) and Dingling (丁零) in the northern regions being conquered and accepting Modu Chanyu as their ruler. The Dingling are described as living proximate to the white ocean which probably means lake Baikal. The Jiankun are described as living nearby, being pastoral peoples (following the herds) with good horses and many mink furs. Both of these are connected to the Kyrgyz in Chinese historical records, such as the book of Tang calling the land of Kyrgyz the former lands of Jiankun (implying descent) but keep in mind these sources come from time periods contemporary to the Kyrgyz. The description of the Jiankun during the book of Han is contemporary to the later Tagar period. Thus it is quite possible that the Jiankun/Gekun of the Han-Xiongnu war were the Tagar.

The Tashtyk as a material culture

Following the Tagar culture, the Tashtyk culture lasts from the first century BC up until the fifth century AD [2]. Almost all the archaeological information acquired about the Tashtyk culture came by way of analysing their grave sites. Just like the preceding Tagar culture, the Tashtyk people practised a combination of animal husbandry and agriculture. An analysis on hair remains suggested that their diet would shift considerably during the seasons. During the summer and autumn there was a considerable consumption of millet, as well as fish, whereas during the other seasons there was a bigger focus on animal products derived from their domesticated stock. The isotope values also indicate there was seasonal mobility, with the Tashtyk population changing habitation areas depending on the season [3].

Another interesting feature about the Tagar and Tashtyk peoples is that they seemed to have domesticated reindeer. These figurines from the Syr Chaatas site not only depict reindeer, they depict reindeer with bridles.

Even earlier is this section from the Bolshaya Boyarskaya Pisanitsa petroglyph of which I had already showcased a section before, which shows a row of reindeer and someone riding one of the animals in the row. This is interpreted to be a reindeer but I’m not sure the petroglyph is clear enough to make that distinction:

Now this is interesting because the Baikal-Sayan region together with the Amur region are considered one of the areas where reindeer domestication, particularly the taiga form of reindeer domestication, had originated. The presence of the domesticated reindeer amongst the Tagar and Tashtyk people could be due to several reasons: Perhaps they adopted the reindeer from their Siberian neighbouring populations which had domesticated it during the bronze age. Another possibility is that the people of the Tagar and Tashtyk peoples domesticated the reindeer independently from other inhabitants of Siberia. Or it could be that these lost peoples actually were the source of reindeer domestication in the region, but that unlike other populations which adopted it it never became a primary livestock.

Some examples of Tashtyk culture clothing:

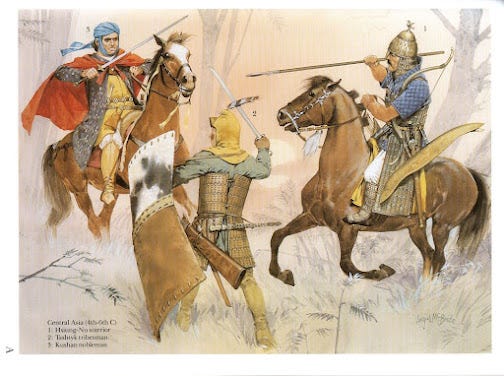

Tashtyk warriors

Here are some images of daggers and a quiver belong to the Tashtyk peoples. These are quite rare finds, because for some reason there hasn’t been a lot of weaponry or armour found within the Tashtyk culture, maybe it is a result of their funeral pyres or their burial practises not including weapons. However we do have some depictions left on items that only got charred rather than fully burned.

We can see that several of the Tashtyk warriors were depicted wearing heavy scale armour. It may be that the armour was made out of leather rather than metal as we have not found any metal parts that could be linked to lamellar armour.

These armour wearing Tashtyk warriors would also employ large shields, which they would use as a protective cover to shoot arrows from or in battle formations similar to the roman infantry. Apparently these shields could be folded in half so they would not be a mobility hindrance.

God I love Angus McBride.

Other Tashtyk warriors are depicted shirtless, and covered in either tattoos or more likely in paint, similar to how other ancient cultures would have done. The patterns displayed below seem to accentuate the muscles on the torso.

But let's not forget the most iconic elements of Scythian cultures, the equestrians. These are also represented in Tashtyk culture petroglyphs.

Burial rites

Another interesting aspect of the Tashtyk culture is the sheer amount of burial rites the culture has. Men, women and children all had different burial rituals, and within the genders and ages there would be differences also. Children would get simple burials in box graves, while being wrapped in linen. Over centuries the preferences for certain rites would shift as well.

The one which stands out to me is the tradition of cremating, followed by the ashes being stuffed into a human doll. This practice was only done by men, and not all men of the Tashtyk culture did this.

This was a form of preserving remains, the other one was mummification. The remains would either get buried in individual box graves, or large crypts which could contain hundreds of people. When these communal crypts were filled the grave would be sealed, often by lighting the wooden framework on fire causing it to collapse on itself.

Masks

The most iconic feature of the Tashtyk culture are probably the burial masks. These masks are how we stumbled upon the Tashtyk culture in the first place. The method of crafting these masks was to place a linen cloth over the face (or at least the eyes and mouth) of the deceased person, and then to apply plaster directly to the face, making a mask that replicates the facial shape of the deceased person to a degree. Sometimes hair or skin would stick to the masks.

Although I cannot recall the source anymore, I’ve seen the mask ritual being described as the Tashtyk people wanting to emulate their “Mongoloid” rulers, and thus displaying themselves in a phenotypically more asiatic image.

Personally I always found that to be extremely silly because we have a very similar mask being worn by the Yingpan man in Xinjiang, who in life was a very wealthy merchant, likey of Sogdian or perhaps Tocharian origin. Another article that came out this year touched on the parallels between the two mask rituals, and also postulates that they have a relation to one another [4].

The Yingpan man in all his glory (also a former avatar of mine):

Perhaps, the masks do not represent a desire for certain phenotypes but may be simply an artistic choice unrelated to “racial”phenotypes. In any case, the parallels between the masks of the Tashtyk and the Yingpan man are interesting, and given that these do not have older common origins I think that the increased connectivity between the areas due to the Xiongnu empire can be an explanation behind this.

Tattoos

The Pazyryk culture is known for their ‘frozen’ tombs with relatively well-preserved bodies, often covered in tattoos. The most famous of undoubtedly being the Siberian Icemaiden, the remains of a wealthy Pazyryk woman.However, the Pazyryk were not the only ones with frozen mummies covered in tattoos, the Tashtyk peoples also practised tattooing.

The tattoos are a bit hard to see on the mummies, and they are more visible through infrared photos.

What is interesting is that some of the designs of the tattoos seem to have parallels with patterns found in artwork of Han dynasty-era China. [5] According to the authors of the article these tattoos were presented in, the designs were likely mediated by the populations of the Tarim Basin, with which the Tashtyk culture seem to have a stronger connection to than their earlier predecessors.

The palace at Abakan

Speaking of Han dynasty-era China, an interesting discovery is that of a palace near Abakan, Khakassia. This palace is not just your average palace, but it was a palace built in Chinese style. Many artefacts of Chinese origin were found around this palace. Other evidence also show pig husbandry and irrigation agriculture, uncommon to the local peoples in the area.

It is unknown who this palace belonged to, but there are several candidates. The first one would be Li Ling, a Han dynasty general who defected to the Xiongnu after having suffered a defeat around the Altai mountains.

Alexey Kovalev suggested that the Palace belonged to the first century Chinese Warlord Lu Fang, who defected towards the Xiongnu as well [6]. Lu Fang came from a tumultuous period and claimed to be a descendant of emperor Wu and thus laying claims to being Emperor himself. Despite the Xiongnu accepting his claims and wanting to put him in charge of northern China, this never came to fruition and Lu Fang moved into Xiongnu territory instead.

Considering that the occupant of the palace is referred to as “Emperor”, as well as some characters used which suggest a date later than the first century BC, the suggestion of Kovalev that this palace belonged to Lu Fang may very well be correct. Lu Fang was an eastern Han dynasty warlord who was a pretender to the throne and then fled to the Xiongnu. Thus it would make sense for the Xiongnu to “acknowledge” him as the emperor of the Eastern Han.

Kyrgyz connection

The Tashtyk culture is followed by the Chataas culture, which has some noticeable differences in terms of material culture. The Chataas culture also has full continuity well into the period that the Yenisei Kyrgyz were described in the historical records. And additionally, we have found Old Turkic inscriptions around Chataas culture sites, leaving no doubts over the ethnolinguistic identity of the bearers of this material culture. The Chataas culture then continues into the Tyuhtyat culture and Askiz culture , which correlate with the period that the Yenisei Kyrgyz started their own khaganate.

From my perspective it would be quite strange for the Tagar peoples to have a linguistic switch during the Tashtyk cultural formation despite the strong biological and cultural continuities, while there not being one for the Tashtyk to Chataas transition which was more significant on both fronts. Whatever language the Tagar spoke (Iranic), it is quite likely the Tashtyk peoples kept speaking that language (Iranic). The succeeding Chataas culture would then be the representative of the Turkophone Kyrgyz obviously.

reconstruction of a Chaatas grave. Cremation was the predominant rite of burial during this phase.

However, just because the Tashtyk in all probability were not the Kyrgyz, that does not mean that there was nothing connecting the two. The Kyrgyz were known for a few things:

Practising a sedentary form of agro-pastoralism in the Minusinsk Basin

Having “Hu” features such as caucasoid faces, light skin and red hair

Having a tradition of adorning their limbs and bodies with tattoos

Doesn’t that remind you a bit of the Tashtyk peoples? It should, because it quite likely is that these elements of the Yenisei Kyrgyz were derived from their Tashtyk culture predecessors.

Another interesting thing is that according to historical records, the ancient Kyrgyz had two beliefs about black hair: the first one is that it meant you were a descendant of Li Ling, the Chinese general previously mentioned.[7] The other was that black hair was a sign of bad luck. Which, if considering that red hair is a recessive trait and the Kyrgyz population would continue to mix with other Turkic peoples as well as their Yeniseian and Samoyedic neighbours, would be a bit of a bad omen as this would naturally decrease the amount of red hair allele carriers relative to the periods of their predecessors. However, it seems that red hair for a few centuries remained relatively prevalent (compared to related peoples) as Persian, Tibetan and Chinese sources all remark on their red hair. I should mention that I suspect what most people called “red hair” would also include auburn or other shades of lighter brown, trending towards red.

During this period, the increasingly cosmopolitan nature of the region was noticeable. While the Tagar culture were relatively “isolated” and lived simple lives as pastoralists, by the time the middle ages commenced the Kyrgyz had large manichean temples and literacy was quite widespread.

Descendants in the modern age

So who can lay claims of blood ties to these ancient sedentary Scythians of Khakassia? Despite the name, the modern day Kyrgyz of the country Kyrgyzstan have little to do with them, as their genetic legacy lies in predominantly in medieval Turkic tribes Central Asia, with the Saka-Wusun period tribes as a strong substrate. Their languages differ too, as Kyrgyz is a Kipchak language related to Kazakh, whereas old Kyrgyz is a Siberian language related to old Uyghur (which is different from modern Uyghur, a Karluk language related to Uzbek) and the Gokturk language.

If we go to the area of the Tashtyk culture, the areas are inhabited by Turkic tribes such as the Khakas, Shors and Chulym. However if you go back a few centuries the Russians called these people Tatars, which was a term for nomad, or when more specific in terms of ethnic identities, Kyrgyz.

Using the Vahaduo Admixture JS tool and the Eurogenes Global25 dataset again, I decided to give a quick breakdown of these populations. After playing around with a several sources, these were the ones that I think were the most fitting. Late_Xiongnu to represent Early Turkic ancestry, RUS_Karasuk_o as a stream of Paleo-Siberian ancestry native to the area, Tagar culture as a representative of Tashtyk, and KAZ_Otyrar_Antiquity to capture any excess southern central asian ancestry.

I tried testing with Kra001 for Uralic-specific ancestry and also several historical East Slavic references, but neither were significantly present and it is hard to say if the small presence was legit or just noise. In any case, leaving it in or out did not have much of an affect on the distances of the models.

Target

Distance

RUS_Late_Xiongnu

RUS_Karasuk_o

RUS_Tagar

KAZ_Otyrar_Antiquity

Altaian

0.01927418

•

78.4

5.0

5.6

11.0

Khakass

0.01551003

•

45.0

26.2

27.8

1.0

Khakass_Kachins

0.01997358

•

65.6

16.6

13.8

4.0

Shor

0.01895739

•

30.0

35.6

33.4

1.0

Shor_Khakassia

0.02589332

•

18.2

47.0

31.4

3.4

Shor_Mountain

0.02444054

•

21.6

42.6

33.2

2.6

Average

0.02067484

•

43.1

28.8

24.2

3.8

I noticed that RISE504, an 8th-10th century sample from the Altai looks quite similar to these populations. Here is a quick model with the same references.

Target: RUS_Altai_IA:RISE504

Distance: 4.2742% / 0.04274210

34.4 RUS_Karasuk_o

33.0 RUS_Late_Xiongnu

19.2 KAZ_Otyrar_Antiquity

13.4 RUS_Tagar

Using this sample as a reference for the Shor seems to work quite well on G25, but not so much for the other populations as they require more Late_XIongnu type input.

Target

Distance

RUS_Altai_IA:RISE504

RUS_Karasuk_o

RUS_Tagar

KAZ_Otyrar_Antiquity

Shor

0.02242086

•

47.8

34.0

18.2

0.0

Shor_Khakassia

0.02482654

•

34.6

42.0

23.4

0.0

Shor_Mountain

0.02245040

•

41.0

37.0

22.0

0.0

Average

0.02323260

•

41.1

37.7

21.2

0.0

This seems to match up quite well with the historical origins of these peoples. The Khakass are generally held to be the direct descendants of the Kyrgyz. The Shors on the other hand came by way of these Kyrgyz tribes mixing with Yeniseian speaking tribes through the middle ages. This extra Yeniseian ancestry in probability is reflected by the amount of ancestry they score from RUS_Karasuk_o. Both the Khakass and Shor score a considerable amount of RUS_Tagar, which is proxying for Tashtyk culture ancestry. This ancestry also could have come from the other eastern Scythian populations but for what it is worth Tagar works the best. The amount of R-Z93 amongst these ethnic groups is quite high, and it wouldn't surprise me if a good amount of those R1a clades are directly from the Tagar and Tashtyk culture peoples.

References

Bokovenko, N. (2006). The emergence of the Tagar culture. Antiquity, 80(310), 860-879. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00094473

Pavel E. Tarasov, Svetlana V. Pankova, Tengwen Long, Christian Leipe, Kamilla B. Kalinina, Andrey V. Panteleev, Luise Ørsted Brandt, Igor L. Kyzlasov, Mayke Wagner - New results of radiocarbon dating and identification of plant and animal remains from the Oglakhty cemetery provide an insight into the life of the population of southern Siberia in the early 1st millennium CE, Quaternary International, Volume 623, 2022, Pages 169-183, ISSN 1040-6182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.12.004.

Shishlina, N., Pankova, S., Sevastyanov, V., Kuznetsova, O., & Demidenko, Y. (2016). Pastoralists and mobility in the Oglakhty cemetery of southern Siberia: New evidence from stable isotopes. Antiquity, 90(351), 679-694. doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.92

Wang, T., Fuller, B.T., Jiang, H. et al. Revealing lost secrets about Yingpan Man and the Silk Road. Sci Rep 12, 669 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04383-5

Pankova, S. V. (2011) - One More Culture with Ancient Tattoo Tradition in Southern Siberia: Tattoos on a Mummy from the Oglakhty Burial Ground, 3rd-4th century AD

Ковалев А.А. Император Китая в хакасской степи // Хунну: археология, происхождение культуры, этническая история. Улан-Удэ: Изд-во БНЦ СО РАН, 2011. С. 77-114. (Kovalev A.A. Emperor of China in the Khakas steppe)

Drompp, M (2002) - The Yenisei Kyrgyz from Early Times to the Mongol Conquest

Some of the images seen above come from these articles and blog entries:

Lifelike face of a tattooed Tashtyk man seen for first time behind a stunning gypsum death mask

A mysterious Chinese-style palace thousands of miles from home in Siberia

Han Era Chinese Palace Found in Southern Russia (1st Century BCE

Kronk library urls (in Russian):